Robot Dreams is part of a tradition of animated films that use no dialogue. To better appreciate this heritage, it’s helpful to consider how Disney approached similar challenges throughout its history.

The Lineage of Dialogue-Free Films and Comparisons with Other Works

Disney’s Challenges

One of the best-known examples is Fantasia (1940). This experimental film combined classical music and animation, telling its story through music and visuals instead of dialogue. The “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” segment with Mickey Mouse is still famous today. Like Robot Dreams uses “September,” Fantasia told its story through music.

Disney’s classic Dumbo (1941) also makes for an intriguing comparison. With its title character never uttering a word throughout the entire film, it became a pioneer in visual storytelling.

Pixar’s Experiment

Pixar’s 2008 film WALL-E also shows the daily life of a lonely robot with almost no dialogue for the first 40 minutes. The filmmakers studied silent film legends like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, proving that “all emotion can be conveyed without words.”

Both WALL-E and Robot Dreams are about a lonely robot finding friendship and love, but there is an important difference. WALL-E ends with a typical Disney happy ending, while Robot Dreams has a more realistic and complex ending.

The Poignant Tale Woven by “September”

One of the film’s most important features is how Earth, Wind & Fire’s “September” runs through the whole story. The song is more than just background music—it represents the heart of the friendship between Dog and the robot and ties the story together.

“Do you remember? / The 21st night of September?” These lyrics resonate deeply with the emotions of the two friends who are separated. Despite the bright, cheerful disco sound, the lyrics speak of love in the past tense. Each time the line “Love was changin’ the minds of pretenders” echoed across the screen, it felt like a tightening in the chest.

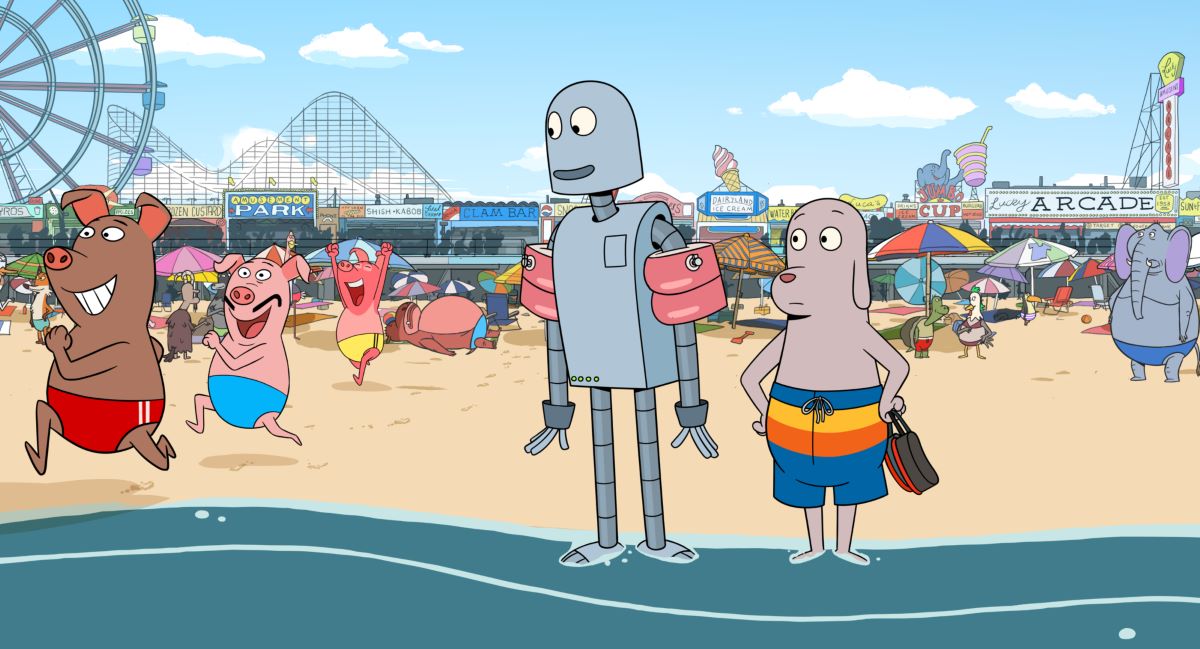

Whether it’s the roller-skating scene in Central Park, the two frolicking on the beach, or the memories after their separation—every time “September” plays in these scenes, different emotions surge. A song that initially evoked joy and fun gradually transforms into a device that stirs sadness and loss.

Other songs used in the film were also memorable. The selection perfectly captures the 1980s atmosphere, featuring Buck Owens’ “(It’s A) Monster’s Holiday,” Booker T & the MG’s “Hip Hug-Her,” and William Bell’s “Happy.” Alfonso de Villalonga’s original score, with its warm, jazz- and Latin-influenced sound, also added depth to the story.

A Love for 1980s New York

Director Pablo Berger arrived in the US in the summer of 1990 to pursue his MFA in film at New York University (NYU), living in New York until 1999. While his residency was in the 1990s, he recounts numerous visits in the 1980s. He recalls, “The New York I lived in no longer exists. Going to the movies is like traveling through time. I wanted viewers to glimpse the 1980s New York I experienced.”

His experiences show up in the film’s details. The dog’s apartment is based on the director’s last real apartment on 13th Street between Avenue A and B. Rent was about $700 back then, but now it’s over five times higher. He also trusted his production partner, Yuko Harami, who worked on locations, research, and music editing: “We were the oldest in the team and New Yorkers. Her information and opinions were truly vital.”

The Manhattan skyline with the Twin Towers, the L train subway (14th Street station), graffiti-laden walls, the iconic rental video store “Kim’s Video,” and TAB soda—these details aren’t passive backgrounds. They serve as memory triggers, channeling the spirit of the 1980s.

The city in the film, filled with animal characters, is diverse and a bit like Zootopia. But unlike Disney movies, the animals here aren’t simply good or bad. Each one feels lonely and wants to connect with others, showing a universal feeling we all share.

Particularly striking was the portrayal of the anonymity and loneliness inherent in New York City. Amidst the bustle of the metropolis, Dog lives alone, unnoticed by anyone. While other rooms visible through windows show couples and families enjoying themselves, only Dog’s room remains dark and silent. This contrast sharply reflects the loneliness experienced by people living in modern cities.

Director Pablo Berger’s Skill and Commitment to Expression

Director Pablo Berger is a Spanish filmmaker known for the live-action film ‘Blancanieves’ (2012). ‘Blancanieves’ is a silent film adaptation of Snow White as a bullfighter’s tale. It was selected as Spain’s entry for the 85th Academy Awards and won 10 Goya Awards.

This wasn’t his first time making a film without dialogue. But using this approach in both live-action and animation is especially impressive.

The director stated that during production, he studied Studio Ghibli works, particularly Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies. His words, “Miyazaki is fantastical, but Takahata is not. I strongly resonated with his storytelling,” convey the dedication to “real emotions” that this film sought to convey.

Emotional Expression Through Eyes and Facial Expressions

The most striking aspect of this film is the characters’ “expressions.” Drawing on his experience in live-action filmmaking, the director was committed to bringing genuine emotion to the animation. “As a live-action director, I wanted to bring great performances to animation too. I wanted to create truthful, emotional, three-dimensional acting. For me, in film, ‘less is more,” he stated.

Notably, the character designs feature almost no shading. Constructed from flat color planes, the characters appear simple at first glance, yet this simplicity draws the audience’s attention directly to expressive features such as eyes and mouths.

The film shows just how much emotion a metal robot can convey through its eyes. When the robot teaches a bird to fly, it simply moves its mouth to show the bird how to fly. The bird finally learns. This moment demonstrates the power of communication without words.

The scenes showing the robot’s dreams are also excellent. Stuck on a sandy beach, the robot keeps dreaming about reuniting with Dog. In the dream, they go home together and are happy again, but when the robot wakes up, it’s still alone on the beach. This cycle of hope and disappointment makes the audience feel what the robot feels.

This meticulous attention to detail captivates viewers for all 102 minutes, even without spoken lines.

Spoilers ahead.

Many viewers likely expect a “Disney-style happy ending.” They imagine the two reuniting, embracing, and starting life together again.

But Robot Dreams does something different. The ending is more nuanced. Even the director said, “Those expecting a Disney-style ending might feel a bit unsettled.”

People have mixed feelings about the ending. Some reviews on Filmarks say, “It wasn’t what I expected” or “I wish it had been a happier ending,” while others praise it: “This ending is precisely why it’s profound” or “It depicts life’s truth.”

The ending resonates deeply because it reflects life’s truths. Not every parting ends in reunion. Not every loss can be recovered. Yet, the memory of what we’ve lost remains in our hearts, shaping us—this message is embedded in the film’s conclusion.

The Dual Meaning of the Dream Scenes

The “Robot Dreams” scenes, which give the film its title, are a crucial element.

Midway through the story, the robot, stranded on a sandy beach, dreams repeatedly of reuniting with Dog. In the dream, Dog comes to rescue it, they return to the apartment together, and happy days begin anew. Yet upon waking, the same unchanging beach stretches before it.

Opinions are divided on this repeated “dream ending” device. Review sites reveal harsh opinions like, “The repeated dream-ending device is painful. You just wake up thinking, ‘Not another dream ending?’”

The repeated dream scenes might make viewers think, “Not again.” But maybe that’s what the director wanted. Each time hope is raised and then lost, the audience feels the robot’s despair all over again.

The final dream scene is the most important. Here, it’s hard to tell what’s real and what’s a dream, making viewers wonder, “Is this real? Or is it a dream?” This choice leaves the ending with complex feelings that linger after the film ends.

Summary: What Friendship Beyond Words Teaches Us

By leaving out dialogue, Robot Dreams actually brings out universal emotions even more strongly.

Loneliness, friendship, loss, memory, and moving forward—these are themes everyone can understand, no matter where they’re from. That’s why this Spanish-French film touched people all over the world, from America to Japan.

The friendship that started with the upbeat song “September” stays with you as a bittersweet memory. Even though their time together didn’t last forever, the memory remains. That’s the message of the film.

This film is for anyone who has said goodbye, remembers someone special, or hopes to meet someone new. Isn’t this gentle, bittersweet 102-minute story something everyone should see?

After watching, you’ll probably want to listen to “September” again. The lyrics will feel different. “Do you remember?”—This simple question now means so much more. The film helps you see just how deep that question can be.